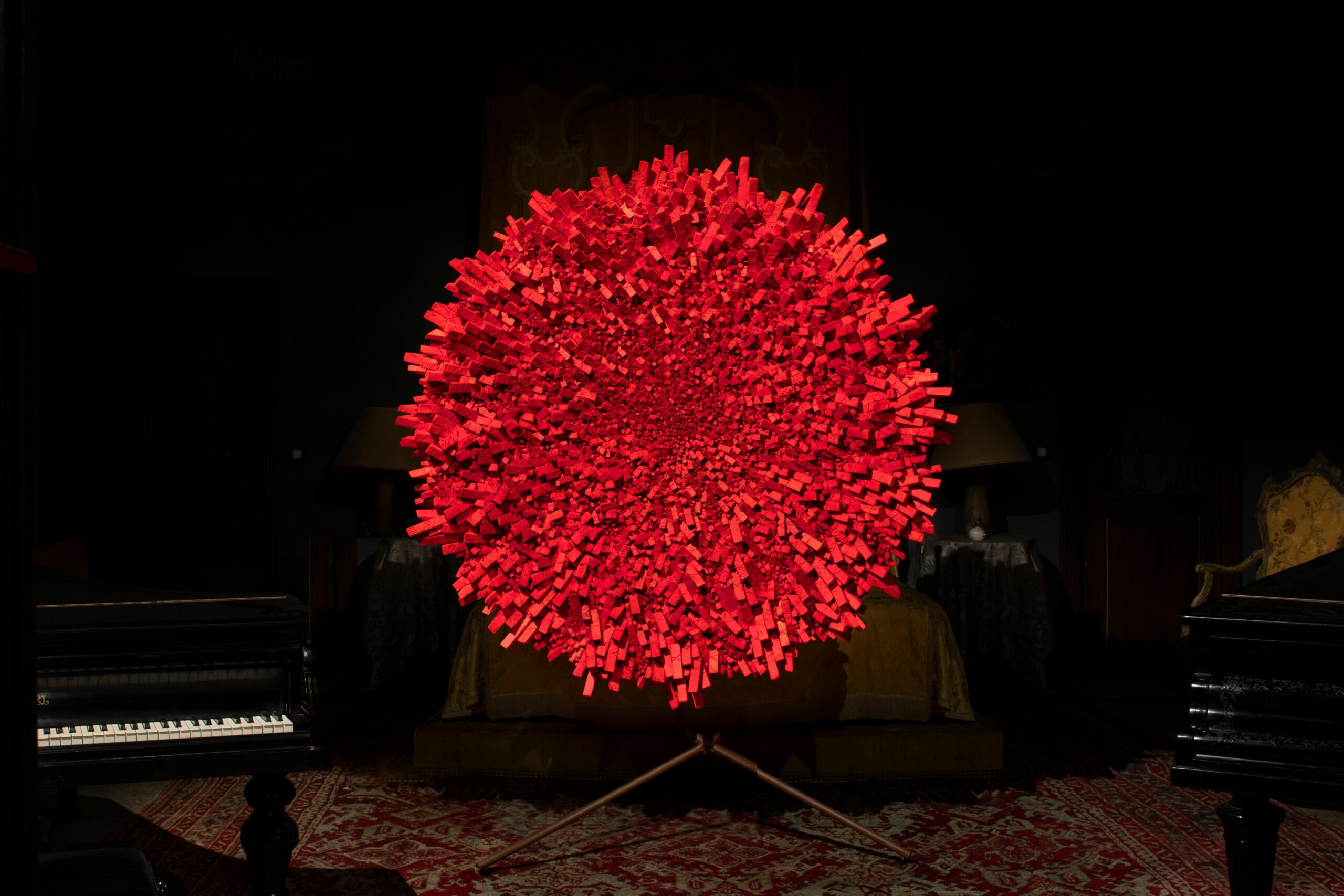

The Korean artist, Chun Kwang Young has been creating reliefs, large scale sculptures and installations for over thirty years named ‘Aggregations.’ These structures are made from thousands of small packages wrapped in handmade text covered Hanji (Korean mulberry paper) and tied together with threads of the paper. This organic material is a champion of ecological reproduction as the tree does not need to be cut down to harvest the paper-making fibers. The process of collecting and dismantling pages of old books made of Hanji followed by the meticulous process of assembling and wrapping each package demands a huge amount of patience. They are an art of healing, presented to the audience as a form of reflection on socio-ecological subjects.

Chun Kwang Young’s recent exhibition at the Venice Biennale ‘Times Reimagined’ confronts the devastating effect humanity has had on our planet. These sculptures are a call to action on the rapid decline of our ecosystems, mass consumption and the destructive levels of pollution in our atmosphere.

Installation views “Chun Kwang Young: Times Reimagined”, 2022, Palazzo Contarini Polignac, Venice. Copyright CKY Studio. Photo: © Alice Clancy

Could you talk about growing up in South Korea and how this might have influenced you and your passion for art?

Looking back, my childhood made a huge impression on how I perceive the world, particularly the beautiful days growing up in my village, the panic of evacuation at the age of 5 due to the outbreak of the Korean War; the lonely study time in Seoul where I had my first exposure to art; and the first prize I won in the national art competition, which encouraged me to pursue higher education in art college. When I was studying, my father heavily opposed my decision to pursue art. He was fully convinced that the only way to be successful was to study business or law. It was the love of my grandparents that supported me through all these difficulties. I still remember the food packed in ‘bojagi’ (a Korean wrapping cloth) that my grandmother prepared for me, which always brought me nostalgic memories of the village Hongcheon when I studied abroad.

After you finished your studies, you focused on Abstract Expressionism. How did this come about and when/why did you shift your creative practice?

My first encounter with American abstract expressionism was in the College of Fine Arts at Hongik University in Seoul. After graduation, I wanted to differentiate myself from the majority of seniors who studied in Europe (especially Paris), so I chose to go to the United States where I learnt more about this genre of art and fell in love with it at my graduate school. At the time, abstract expressionism resonated with my inner desire for free expression, accentuated by the astonishing reality of social upheavals in contrast with rosy ideals. In a way abstract expressionism worked best to express the chaos and struggles of the world I lived in.

However, there had always been a haunting voice in my mind, asking myself if there could be a better way to reveal my own identity, both in form and in spirit. In 1995, I suffered from a nasty cold and it brought back childhood memories of the medicine packages wrapped in mulberry paper hanging from the ceiling of the traditional Korean herbal clinic. It was during this time that I began to explore the creative practice of working with this material.

Why did you begin working with mulberry paper? Could you talk about why this material is important to you?

Hanji (Korean mulberry paper) is much more than a material, because it has been part of my whole life. The hanok (traditional Korean style house) I lived in when I was born was built with mud walls covered with hanji; all the books used in seodang (village school) where I learnt the Thousand Character text were made in hanji; and the herbal medicines hanging from the ceiling in my uncle’s oriental medicine shop were wrapped in hanji.

Hanji is a medium for me to express my perception and contemplation of social, cultural and ecological struggle and reconciliation. Moreover, I see the life cycle of living entities through the production and recycling of the mulberry paper.

For the past 30 years, you have researched and practiced under the theme of interconnectedness. Could you explain further what this means?

In ecology, interconnectedness is an absolute factor for the reproduction and survival of all living things, including humans, and it means an essential requirement for ensuring biodiversity and enhancing sustainability in adverse conditions such as climate change. Therefore, interconnectedness is the healing DNA that overcomes the oppression and loss that arise from social disconnection, both in space and in time. It is also a thought-provoking process looking closely into the durability and recycling of the mulberry paper which reveals the natural laws of ecology facilitated by a biodiverse environment.

Your recent exhibition at the Venice Biennale ‘Times Reimagined’ showcases your extraordinary monumental sculptures and installations, could you talk about your creative process and what ‘Aggregation’ means?

‘Aggregation’ was born from my concern of the increasing level of heinous crimes, terrorism, wars, and the destruction of the natural environment. It was important that my work responded to this.

Hanji triangular bojagi (a Korean wrapping cloth) are hand-wrapped and tied one by one, so that none of them are exactly the same. This tenacious work embodies the mindset of covering the wounds of each individual, nature, and all the living beings. In some cases, I use discarded trash that is not easily recycled in nature to fill the triangular-shaped package wrapped in Hanji. In other words, it is a way to heal and reuse environmentally polluting materials.

Most of the paper existed as a book before it was used for artwork. I acquire old books, mostly genealogy books, disassemble them, and make triangular-shaped packages with the paper that has been passed on through many hands in the process of paper-making, selling, reading and recycling.

On average how long does it take to make each relief?

The smallest work displayed in Venice this time, for instance 195cm x 131cm, takes about two months to complete if all materials are ready.

Could you talk about the central themes of the exhibition and why it was important for you to share your work with the public?

‘Times Reimagined’ is a periodic review of my practice through the more intense lens of ecology. Given the unique Renaissance-style palazzo, most of the large-scale installations required site-specific adaptation, which was not just a challenge but an exciting process of initiating a new dialogue between the works and the space. Furthermore, the audience reception and interaction breathed new life into my works, adding another layer of ‘aggregation.’